letters to emerson - on being curious and morally present

be a person of so much integrity that mary oliver would want to write you a love poem in your memory

I have never read Ralph Waldo Emerson’s work before — at least not yet, because I just ordered Nature for $3 on World of Books, which is an addicting new discovery of mine that sells books for cheap cheap cheeaapppp.

I have been slowly working my way through Upstream by Mary Oliver, as many of you may know from all the essays I have written dedicated to her words.

I am at the third part of her book of essays, where she writes about her “friends,” the people who have inspired her and comforted her across time through their writings, such as Emerson, Frost, Whitman, and Poe.

Oliver’s essay on Emerson reads more like a love letter than a simple factual essay or biography. And, while reading it, I realized that her descriptions of Emerson were how I would want someone to describe me. She described a man who was thoughtful, communal, expansive, and intelligent. She described a man who was devoted to curiosity, but not to seriousness.

When I’m gone, I want to be remembered as devoted.

The labor of Emerson’s life was the life of his mind. He believed that a person’s “inclination, once awakened to it, would be to turn all the heavy sails of [their] life to a moral purpose.”

Morality and ethics have been a core part of my pondering as of late. Like most people, I want to be a “good person.” But, what does it actually mean to be a good person? For most of my life, I have classified being a good person by how pleased others are with me. My worth, my morality, my very existence was only “good” when others labeled me as good.

I am coming to understand that this does not make a person good — it makes a person fragmented, inauthentic, and intangible. It is a consensual dissolution of the self. To attempt to be a person’s ideal person is to not be a real person at all. By attempting to be good, I am stripping myself of my humanity. I was worried more about approval than I was morality. And, the more I reflected on morality, the more I realized that people pleasing could very rarely, if ever, overlap with authenticity, ethics, and morality.

Emerson was sure that each person is “utterly important and limitless.” Emerson wrote, “Attachment to the Ideal, without participation in the world of [humans], was the business of foxes and flowers, not [people.]” If this is true, it means a few things.

Every person has a unique set of beliefs, thoughts, actions, and code of ethics.

Every unique set of beliefs, thoughts, actions, and codes of ethics are valid and respectable.

There is no absolute right or absolute wrong.

Aiming for an absolute right or absolute wrong will leave you frazzled, lost, and rigid.

It can be an easy next step to apply a strong sense of justice to morality, especially for those like me, who are kind of just now dedicating themselves to this journey. It can be difficult to separate discernment from judgment. At times, it’s helpful and even healthy to witness what others do and decide if you agree with it or not. Learning from others is how we practice and grow our own beliefs. However, this presents a slippery slope to judging others harshly, creating hierarchies of right and wrong, and creating obsession.

Emerson believed in justice just as much as he did morality, but he did not seem to narrow his vision of morality to a duality of rights and wrongs. He did not view morality as rigid absolutes. Perhaps this was because he was confident in his own actions and beliefs — for, if you are confident in your own moral compass, why would you worry yourself with the compass of another? He was not in the practice of proving himself to others, which also meant that he didn’t feel a need to defend, guard, or judge morality.

“What you do speaks so loudly that I cannot hear what you say.”

― Ralph Waldo Emerson

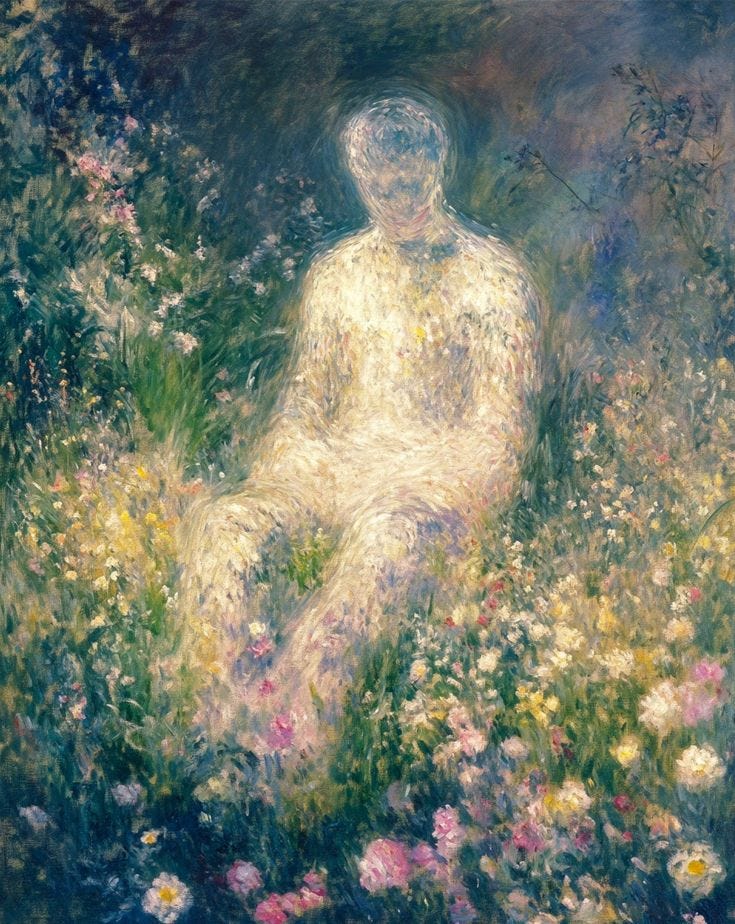

All of this brings up a core and repeated dilemma surfacing in my life — the tension between solitude and connection, between being good for others and good to myself. Emerson believed that the heart’s spiritual awakening is the true work of our lives, writing that “this is the beginning of paradise here among the temporal fields.”

It is not just the mind’s spiritual awakening, but the heart’s.

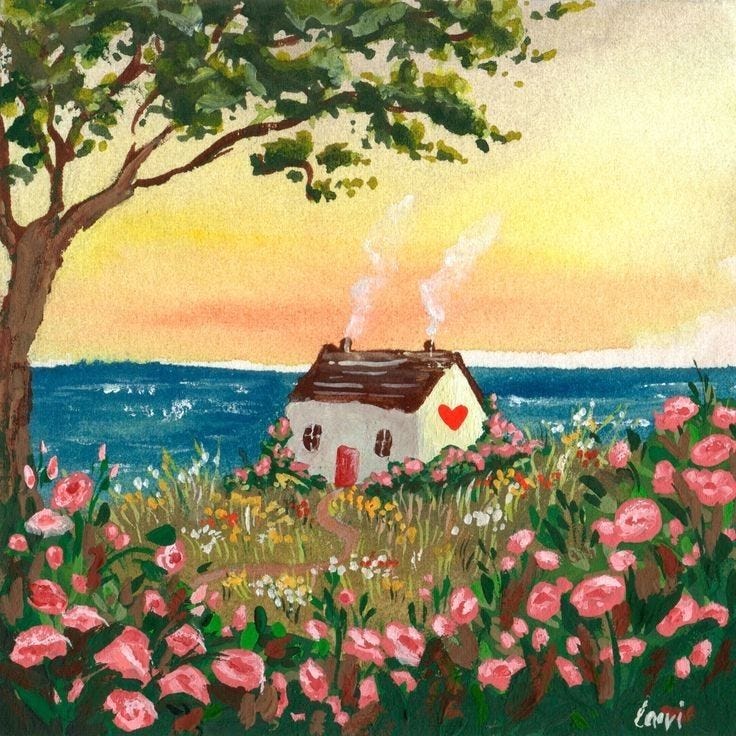

I want to be someone whose house “was often full of friends and talk,” as Oliver described Emerson. I often feel pulled in two directions, one where I am a lively and flexible person surrounded by loved ones, and one where I am hibernating in my den of reflection and candlelight.

In my essay, letters to craving solitude and building community, I wrote about this, saying:

In a world where the therapy-speak advice of setting rigid boundaries (although boundaries are for us to make and keep, not rules for others to follow, but that’s a different essay), cutting them off, protecting your peace (gag), and other avoidant things, is everywhere, it’s hard for me to decipher a good balance. Because I do think that it’s important for me, and every person, to honor their limits, needs, and general desires. And, I think we need to embrace a certain amount of inconvenience and discomfort for things (and people) that matter. I think there are times when strict bedtimes are to be honored, and others where maybe getting 6 hours if it means having beautiful, joyful, and expansive connection. Having an open mind and a non-judgmental attitude toward others is extremely important, and so is having discernment and holding your own boundaries as guidance for your decisions… You get to decide your values and the importance you place on each one. Which is making me realize, maybe I need to put in “solitude” or “softness” into my values list. I won’t take out “community,” but maybe alone time needs a spot in there too, because it is important to me, even if I feel ashamed of it. (Which I don’t think I should, by the way, but still.)

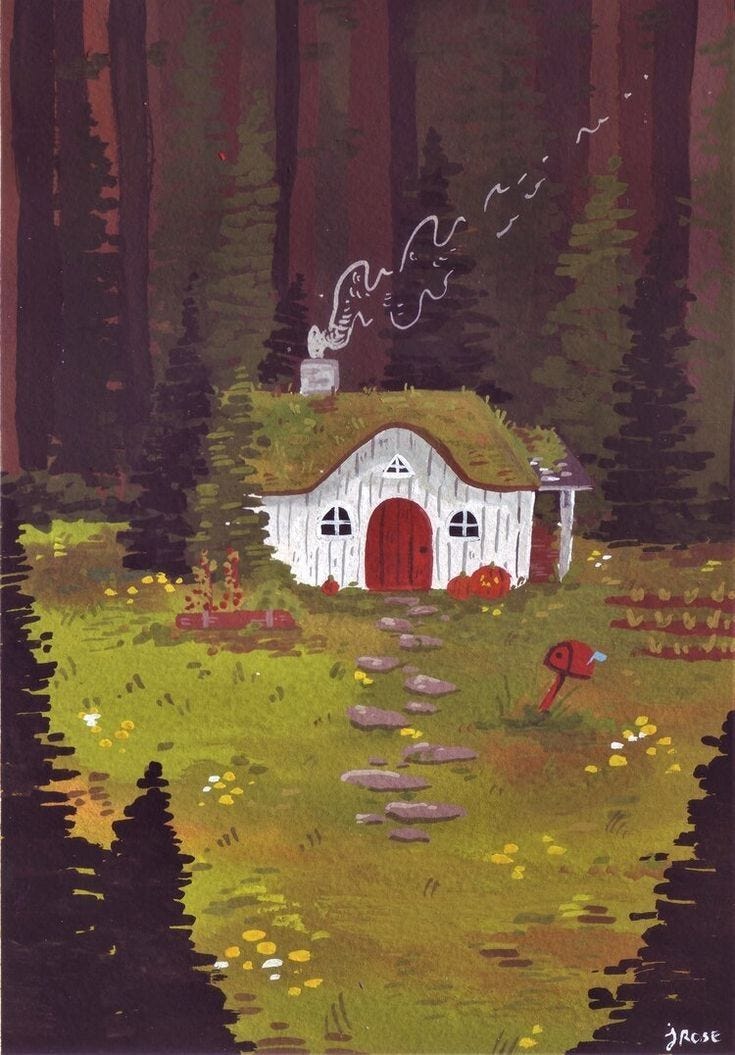

In that essay, I even quoted another passage from Oliver’s Upstream: “For me it was important to be alone; solitude was a prerequisite to being openly and joyfully susceptible and responsive to the world of leaves, light, birdsong, flowers, flowing water.”

On more than one occasion, [Mary Oliver] talks about the importance of her solitude and quiet life as not just ideal but required landscape of her creativity and thoughtfulness.

Her companions were the animals and the nature around her, as well as the thoughtful authors of books that became her North star.

No amount of shame or “shoulds” or articles I read about the importance of community makes my tender ache of solitude any less potent.

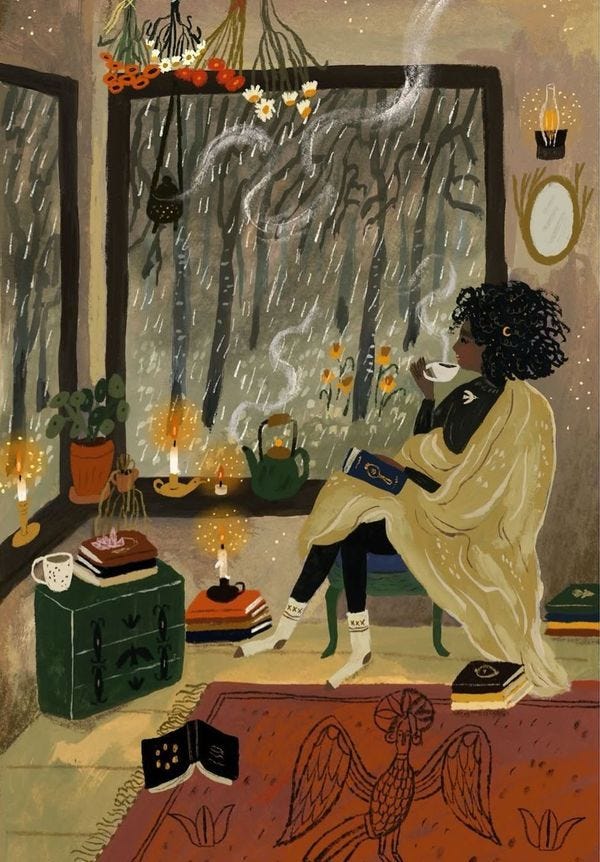

I’ve been searching for balance, searching for how I can be at home with myself, while also sharing that home with others. Emerson wrote that the greater energies of life find sustenance in the richness and steadfastness of inner life — which is to say that perhaps one must create a home within themselves first, a place of solace we can return to every night, once our beloved guests ultimately depart. Our inner home should be cultivated lovingly, with ornate rugs and soft blankets, walls covered with the artwork that came from our own fingers and minds. This is where the scrolls of deliberation lie, where we sort through the things that others have shared, where we put some things in the Agree bin, and the others in the Disagree, but Appreciate The Thought bin. It is in this home of our own that we sit alone by the fire and debrief. It is this home that provides us the safe container to process and deliberate. It is this inner home that we have a bountiful garden of vegetables and herbs for hearty soups and rows of jars for herbal teas and remedies. We have all we need here to sustain ourselves, and we should be homebodies in the coziness of our minds.

And, homes are made for hosting, or even more boldly, to leave. Homes are made with doors that open, welcome mats that greet, and plush sofas and comfortable chairs to accommodate guests. Homes are made with locks for keys, so that we may put on our shoes and hat and venture outside for a while. We must forage if we expect to have anything new to bring home.

“It is easy in the world to live after the world's opinion; it is easy in solitude to live after our own; but the great man is he who in the midst of the crowd keeps with perfect sweetness the independence of solitude.”

― Ralph Waldo Emerson, The Complete Prose Works Of Ralph Waldo Emerson

Oliver wrote, “Emerson would not turn from the world, which was domestic, and social, and collective, and required action. Neither would he swerve from that imperturbable inner radiance, mystical, forming no rational word but drenched with passionate and untranslatable song.” She wrote that he believed that a person should be “domestic, steady, moral, politic, reasonable,” and also “subsumed, whirled, to know [themselves] as dust in the fingers of the wind.”

So then, I too will not turn away from the world. I will not lock my doors and windows and cover them with boards so that no one can enter — or leave. I will allow fresh air to circulate in my living room, I will dry my linens outside, I will offer my guests lemonade and coffee and tea and a fresh slice of bread with honey and jam and butter. I will tend to my inner home and enjoy how it sounds when no one is in it, and also how it sounds when it is bustling with laughter, music, and discussion.

And I will remind myself that neither state is better than the other, as I make myself a mug of hot chocolate in my inner home and come back to my own devotion.